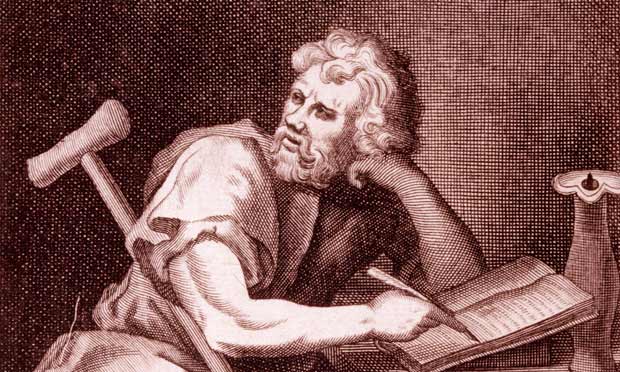

In our Brisbane Stoics meetup in February, we started exploring the Discourses.

In this video, I outline the core concepts of 1.1

Concerning what is in our power and what is not

Discourses: Hard Translation-

Introduction

“In 1.1 Epictetus begins by presenting the reasoning faculty as the one which, unlike other arts and faculties, comprehends both itself and the other faculties. He then isolates one salient aspect of this faculty, ‘which enables us to make right use of our impressions’, which encapsulates this combination of self-management and management of other things. The latter capacity is described, by contrast with our bodily condition, possessions, and personal relationships, as the only thing that is wholly ‘up to us’ or ‘within our power’ ( eph’ hēmin ). This idea is presented by saying that this capacity (which is ‘a portion’ of divinity) is the only one that Zeus, king of the gods, could place wholly within our power (10–13, expressed as a speech by Zeus).

Epictetus goes on to maintain that, typically, we misuse this capacity; we concern ourselves with the things that are not ‘up to us’ (possessions and so on). Instead, we should ‘make the best of what lies within our power and deal with everything else as it comes’. This recommendation is then illustrated by a series of imagined dialogues, some of them involving historical figures, including famous Stoicism-inspired examples of resistance to tyrannical attitudes or actions by Roman emperors. Each of these is designed to show what is involved in ‘making the best of what lies within our power’, and at the same time ‘dealing with everything else’ as regards our body or continued life — ‘as it comes’. These examples show, as he points out, ‘what it means to train oneself in the matters in which one ought to train oneself’” p. xxii.

A.A. Long, ‘Epictetus a Stoic and Socratic guide to Life’ p. 27.

Four principal concepts give Epictetus’ philosophy its unity and coherence: freedom, judgement, volition, and integrity.

Freedom

The freedom that interests Epictetus is entirely psychological and attitudinal. It is freedom from being constrained or impeded by any external circumstance or emotional reaction. He diagnoses unhappiness as subservience to persons, happenings, values, and bodily conditions, all of which involve the individual subject in surrendering autonomy and becoming a victim to debilitating emotions. Happiness, by contrast, is unimpededness, doing and experiencing only what you want to do and experience, serenity, absence of any sense that things might be better for you than you find them to be.

Judgement

The basis for this ideal of freedom brings us to the second core concept, JUDGEMENT. Following his Stoic authorities, Epictetus regards all mental states, including emotions, as conditioned by judgements… On this model of mind, there is no such thing as a purely reactive emotion or at least a reaction that we cannot, on reflection, control. How we experience the world, and how we experience ourselves, depends through and through on the judgements we form, judgements about the structure of the world, the necessary conditions of human life, goodness, badness, and, above all, what is psychologically ‘up to us’. The crucial idea is that we do not experience the world without the mediation of our own assessments.

This rationalistic analysis of emotions and evaluations implies that they themselves, and the judgements on which they depend, are completely in our power, up to us, within the control of our will.

Volition

The crucial idea is that volition is what persons are in terms of their mental faculties, consciousness, character, judgements, goals, and desires: volition is the self, what each of us is, as abstracted from the body…

You and I are not our bodies, nor even do we own our bodies. We, our essential selves, are our volitions. In that domain, and only in that domain, we have the possibility of freedom…

What is required of anyone who wants genuine freedom is to transfer all wants, values, and attachments away from externals and situate them within the scope of one’s volition. Prohairesis or volition is the locus of all that truly matters to humans who have understood cosmic order and their own natures and capacities. Its perfection is the human good, and the goal of Epictetus’ teaching.

Like earlier Stoics, he holds that goodness and badness in the strict sense pertain only to what accords or fails to accord with our essential human nature: that is to say, our nature as rational animals. A perfected volition, then, is good in this strict sense, and no other objective is comparably deserving. Consequently, everything that falls outside the individual’s volition, including family, status, country, the condition of one’s body, material prosperity-all of these are inessential to its perfection and the freedom or happiness that this perfection constitutes. Not only are these things inessential, but also attachment to them is a certain recipe for disappointment, anxiety, and unhappiness.

Integrity

I use this word to translate a cluster of terms Epictetus repeatedly uses that can be rendered by such words as shame, reverence, trustworthiness, conscience, decency. Integrity is as much a part of Epictetus’ normative self as a good volition; in fact, it is not distinct from a good volition but the way that that mental disposition is disposed in relation to other persons…

Volition, as one’s self, is where one’s interests lie. It determines what one calls ‘I’ and ‘mine’. A good volition, because it values itself over everything else, includes integrity; it treats integrity as essential to its own interests. Integrity involves honouring all of one’s ties to kin, social roles, and other acquired relationships…

[Epictetus] is a moralist, not because he sets out from a position ·with regard to our duties to other persons, but because his bedrock principle of cultivating the self as a good volition entails uncompromising integrity (respect, cooperation, justice, and kindliness) with respect to every human being one encounters or is by family or circumstance related to.

Will Johncock- ‘Beyond the Individual’.

We are a trace of the whole rationality (quote p. 49)

BOOK 1 Epictetus ‘Discourses’

1.1 About things that are within our power and those that are not

[1] Among all the arts and faculties, you’ll find none that can take itself as an object of study, and consequently none that can pass judgement of approval or disapproval upon itself. [2] In the case of grammar, how far does its power of observation extend? Only as far as to pass judgement on what is written. And in the case of music? Only as far as to pass judgement on the melody. [3] Does either of them, then, make itself an object of study? Not at all. If you’re writing to a friend, grammar will tell you what letters you ought to choose, but as to whether or not you ought to write to your friend, grammar won’t tell you that. And the same is true of music with regard to melodies; as to whether or not you should sing or play the lyre at this time, that is something that music won’t tell you. [4] What will tell you, then? The faculty that takes both itself and everything else as an object of study. And what is that? The faculty of reason. For that alone of all the faculties that we’ve been granted is capable of understanding both itself — what it is, what it is capable of, and what value it contributes — and all the other faculties too. [5] For what else is it that tells us that gold is beautiful? For the gold itself doesn’t tell us. It is clear, then, that this is the faculty that has the capacity to deal with impressions. [6] What else can judge music, grammar, and the other arts and faculties, and assess the use that we make of them, and indicate the proper occasions for their use? None other than this. [7] It was fitting, then, that the gods have placed in our power only the best faculty of all, the one that rules over all the others, that which enables us to make right use of our impressions; but everything else they haven’t placed within our power. [8] Was it that they didn’t want to? I think for my part that, if they could, they would have entrusted those other powers to us too; but that was something that they just couldn’t do. [9] For in view of the fact that we’re here on earth, and are shackled to a body like our own, and to such companions as we have, how could it be possible that, in view of all that, we shouldn’t be hampered by external things? [ 10 ] But what does Zeus * have to say about this? ‘If it had been possible, Epictetus, I would have ensured that your poor body and petty possessions were free and immune from hindrance. [11] But as things are, you mustn’t forget that this body isn’t truly your own, but is nothing more than cleverly moulded clay. [12] But since I couldn’t give you that, I’ve given you a certain portion of myself, this faculty of motivation to act and not to act, of desire and aversion, and, in a word, the power to make proper use of impressions; if you pay good heed to this, and entrust all that you have to its keeping, you’ll never be hindered, never obstructed, and you’ll never groan, never fi nd fault, and never fl atter anyone at all. [13] What, does all of that strike you as being of small account?’ Certainly not. ‘So you’re content with that?’ I pray so to the gods. [14] But as things are, although we have it in our power to apply ourselves to one thing alone, and devote ourselves to that, we choose instead to apply ourselves to many things, and attach ourselves to many, to our body, and our possessions, and our brother, and friend, and child, and slave. [15] And so, being attached in this way to any number of things, we’re weighed down by them and dragged down. [16] That is why, if the weather prevents us from sailing, we sit there in a state of anxiety, constantly peering around. ‘What wind is this?’ The North Wind. And what does it matter to us and to him? ‘When will the West Wind blow?’ When it so chooses, my good friend, or rather, when Aeolus chooses; for God hasn’t appointed you to be controller of the winds, he has appointed Aeolus. [17] What are we to do, then? To make the best of what lies within our power, and deal with everything else as it comes. ‘How does it come, then?’ As God wills. [18] ‘What, am I to be beheaded now, and I alone?’ Why, would you want everyone to be beheaded for your consolation? [ 19 ] Aren’t you willing to stretch out your neck as Lateranus did at Rome when Nero ordered that he should be beheaded? For he stretched out his neck, received the blow, and when it proved to be too weak, shrank back for an instant, but then stretched out his neck again. [ 20 ] And moreover, on an earlier occasion, when Epaphroditus * came to him and asked him why he had fallen out with the emperor, he replied, ‘If I care to, I’ll explain that to your master.’ [21] What, then, should we have at hand to help us in such emergencies? Why, what else than to know what is mine and what isn’t mine, and what is in my power and what isn’t? [22] I must die; so must I die groaning too? I must be imprisoned; so must I grieve at that too? I must depart into exile; so can anyone prevent me from setting off with a smile, cheerfully and serenely? ‘Tell me the secrets.’ [23] I won’t reveal them; for that lies within my power. ‘Then I’ll have you chained up.’ What are you saying, man, chain me up? You can chain my leg, but not even Zeus can overcome my power of choice. [24] ‘I’ll throw you into prison.’ You mean my poor body. ‘I’ll have you beheaded.’ Why, did I ever tell you that I’m the only man to have a neck that can’t be severed? [25] These are the thoughts that those who embark on philosophy ought to refl ect upon; it is these that they should write about day after day, and it is in these that they should train themselves. [ 26 ] Thrasea * was in the habit of saying, ‘I’d rather be killed today than be sent into exile tomorrow.’ [ 27 ] So what did Rufus * say in reply? ‘If you choose death as being the heavier misfortune, what a foolish choice that is; if you choose it as being the lighter, who has granted you that choice? Aren’t you willing to be content with what is granted to you?’ [ 28 ] So what was it that Agrippinus * used to say? ‘I won’t become an obstacle to myself.’ The news was brought to him that ‘your case is being tried in the Senate’. [29] — ‘May everything go well! But the fi fth hour has arrived’ — this was the hour in which he was in the habit of taking his exercise and then having a cold bath — ‘so let’s go off and take some exercise.’ [30] When he had completed his exercise, someone came and told him, ‘You’ve been convicted.’ — ‘To exile,’ he asked, ‘or to death?’ — ‘To exile.’ — ‘What about my property?’ — ‘It hasn’t been confi scated.’ — ‘Then let’s go away to Aricia and eat our meal there.’ [31] This is what it means to train oneself in the matters in which one ought to train oneself, to have rendered one’s desires incapable of being frustrated, and one’s aversions incapable of falling into what they want to avoid. [32] I’m bound to die. If at once, I’ll go to my death; if somewhat later, I’ll eat my meal, since the hour has arrived for me to do so, and then die afterwards. And how? As suits someone who is giving back that which is not his own.

Gorgias– Plato.

SOCRATES: I believe that I’m one of a few Athenians—so as not to say I’m the only one, but the only one among our contemporaries—to take up the true political craft and practice the true politics. This is because the speeches I make on each occasion do not aim at gratification but at what’s best. They don’t aim at what’s most pleasant. And because I’m not willing to do those clever things you recommend, I won’t know what to say in court. And the same account I applied to Polus comes back to me. For I’ll be judged the way a doctor would be judged by a jury of children if a pastry chef were to bring accusations against him. Think about what a man like that, taken captive among these people, could say in his defense, if somebody were to accuse him and say, “Children, this man has worked many great evils on you, yes, on you. He destroys the youngest among you by cutting and burning them, and by slimming them down and choking them he confuses them. He gives them the most bitter potions to drink and forces hunger and thirst on them. He doesn’t feast you on a great variety of sweets the way I do!”

What do you think a doctor, caught in such an evil predicament, could say? Or if he should tell them the truth and say, “Yes, children, I was doing all those things in the interest of health,” how big an uproar do you think such “judges” would make? Wouldn’t it be a loud one?

CALLICLES: Perhaps so.

SOCRATES: I should think so! Don’t you think he’d be at a total loss as to what he should say?

CALLICLES: Yes, he would be.

SOCRATES: That’s the sort of thing I know would happen to me, too, if I came into court. For I won’t be able to point out any pleasures that I’ve provided for them, ones they believe to be services and benefits, while I envy neither those who provide them nor the ones for whom they’re provided. Nor will I be able to say what’s true if someone charges that I ruin younger people by confusing them or abuse older ones by speaking bitter words against them in public or private. I won’t be able to say, that is, “Yes, I say and do all these things in the interest of justice, my ‘honored judges’”—to use that expression you people use—nor anything else. So presumably I’ll get whatever comes my way.

CALLICLES: Do you think, Socrates, that a man in such a position in his city, a man who’s unable to protect himself, is to be admired?

SOCRATES: Yes, Callicles, as long as he has that one thing that you’ve often agreed he should have: as long as he has protected himself against having spoken or done anything unjust relating to either men or gods. For this is the self-protection that you and I often have agreed avails the most. Now if someone were to refute me and prove that I am unable to provide this protection for myself or for anyone else, I would feel shame at being refuted, whether this happened in the presence of many or of a few, or just between the two of us; and if I were to be put to death for lack of this ability, I really would be upset. But if I came to my end because of a deficiency in flattering oratory, I know that you’d see me bear my death with ease. For no one who isn’t totally bereft of reason and courage is afraid to die; doing what’s unjust is what he’s afraid of.

For to arrive in Hades with one’s soul stuffed full of unjust actions is the ultimate of all bad things. If you like, I’m willing to give you an account showing that this is so.

Conclusion

(following the letter)

Although this letter is an extreme case of taking Epictetus’ philosophy regarding ‘what is in our control’ to mean something that is definitely not intended, it is important to point out that such an observation is not entirely trivial. It is clearly possible that a modern Stoic readership, interpreting through the lens of self-help and positive forms of psychology may come to such a conclusion. As noted by Will Johncock in his recent book “Beyond the Individual” (2023)

“There is something shared between our mind and an entire universe and therefore between our mind and other human’s minds. This unsettles straightforward oppositional distinctions between what is supposedly internal versus external to the self. Such considerations might duly spark discussions that unsettle the branding of stoicism as a tool that individuals can use to mentally defy an anxiety inducing ‘out there’ world. There is a voracious appetite in the self-help market for reductions of Stoic philosophy to assertions around mental self-definition and personal control. Such adaptions must be complemented though with the kind of reading… which appreciates that for the Stoics, your rational mind is dispersed in and among other people’s minds. If what is mental has shared roots and operations, then mental control is a collaborative exercise.” p. 49.

This idea, that our individual rationality is grounded beyond us collectively, or even in a universal form of rationality, what the Stoics call Reason, or Zeus, recalls Hard’s comment cited earlier, that

“Epictetus’ treatment sometimes has distinctive emphases. One is our capacity for rational agency, and a second our capacity for ethical (especially social) development; a third is the idea that these capacities form key distinctive features of human nature within the framework of a divinely shaped universe”.

Likewise, Pierre Hadot in his ‘philosophy as a way of life’ emphasises the uniqueness of the Stoic perspective, as an attempt to transform one’s consciousness above and beyond our individual and entirely subjectively concerned experience- by rejecting our instinctual tendency to accept on face value the appearance of things and rather to take an objective or cosmic view. Such a view takes the world to be a living cosmic animal of which we are a part. Reason as God is throughout the universe and for us to live according to virtue it is incumbent on us to see beyond immediate self-preserving appearances of things and live in ways that actualise our rational ends. Such an approach to life is the best defense against vicissitude and misfortune. We find Socrates himself making similar claims when he defends philosophy’s noble requirements in his arguments with Callicles-

SOCRATES: I believe that I’m one of a few Athenians—so as not to say I’m the only one, but the only one among our contemporaries—to take up the true political craft and practice the true politics. This is because the speeches I make on each occasion do not aim at gratification but at what’s best. They don’t aim at what’s most pleasant. And because I’m not willing

to do those clever things you recommend, I won’t know what to say in court. And the same account I applied to Polus comes back to me. For I’ll be judged the way a doctor would be judged by a jury of children if a pastry chef were to bring accusations against him. Think about what a man like that, taken captive among these people, could say in his defense, if somebody were to accuse him and say, “Children, this man has worked many great evils on you, yes, on you. He destroys the youngest among you by cutting and burning them, and by slimming them down and choking them he confuses them. He gives them the most bitter potions to drink and forces hunger and thirst on them. He doesn’t feast you on a great variety of sweets the way I do!”

What do you think a doctor, caught in such an evil predicament, could say? Or if he should tell them the truth and say, “Yes, children, I was doing all those things in the interest of health,” how big an uproar do you think such “judges” would make? Wouldn’t it be a loud one?

CALLICLES: Perhaps so.

SOCRATES: I should think so! Don’t you think he’d be at a total loss as to what he should say?

CALLICLES: Yes, he would be.

SOCRATES: That’s the sort of thing I know would happen to me, too, if I came into court. For I won’t be able to point out any pleasures that I’ve provided for them, ones they believe to be services and benefits, while I envy neither those who provide them nor the ones for whom they’re provided. Nor will I be able to say what’s true if someone charges that I ruin younger people by confusing them or abuse older ones by speaking bitter words against them in public or private. I won’t be able to say, that is, “Yes, I say and do all these things in the interest of justice, my ‘honored judges’”—to use that expression you people use—nor anything else. So presumably I’ll get whatever comes my way.

CALLICLES: Do you think, Socrates, that a man in such a position in his city, a man who’s unable to protect himself, is to be admired?

SOCRATES: Yes, Callicles, as long as he has that one thing that you’ve often agreed he should have: as long as he has protected himself against having spoken or done anything unjust relating to either men or gods. For this is the self-protection that you and I often have agreed avails the most. Now if someone were to refute me and prove that I am unable to provide this protection for myself or for anyone else, I would feel shame at being refuted, whether this happened in the presence of many or of a few, or just between the two of us; and if I were to be put to death for lack of this ability, I really would be upset. But if I came to my end because of a deficiency in flattering oratory, I know that you’d see me bear my death with ease. For no one who isn’t totally bereft of reason and courage is afraid to die; doing what’s unjust is what he’s afraid of.

For to arrive in Hades with one’s soul stuffed full of unjust actions is the ultimate of all bad things. If you like, I’m willing to give you an account showing that this is so.

So although Epictetus’s prohairesis is concerned with the control that we have over the rational faculty, awareness of control is only part of the philosophical process. And following Socrates demonstration of his understanding that the best defense in life is not merely to live as long as possible, or to have as much wealth or success as possible, but to live a life that honours both Gods and Men. That is, to pay attention to oneself as a being whose own nature is grounded in universal reason- first and foremost- and whose own individuality is but a trace of the order and coherence of Reason that penetrates, motivates and vitalises the Cosmos throughout. From this perspective it might be argued that Stoicism aims to educate us in the correct use of reason in forming judgements about the value and use of things.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.